Before Ted Lasso, there was Terry Smith. And English soccer’s first American owner appeared to have a Lasso-esque plan ready to roll on day one.

But, as Kevin Ratcliffe, then-manager of Chester City, explained to theScore, there was one problem: Smith didn’t have a clue about soccer.

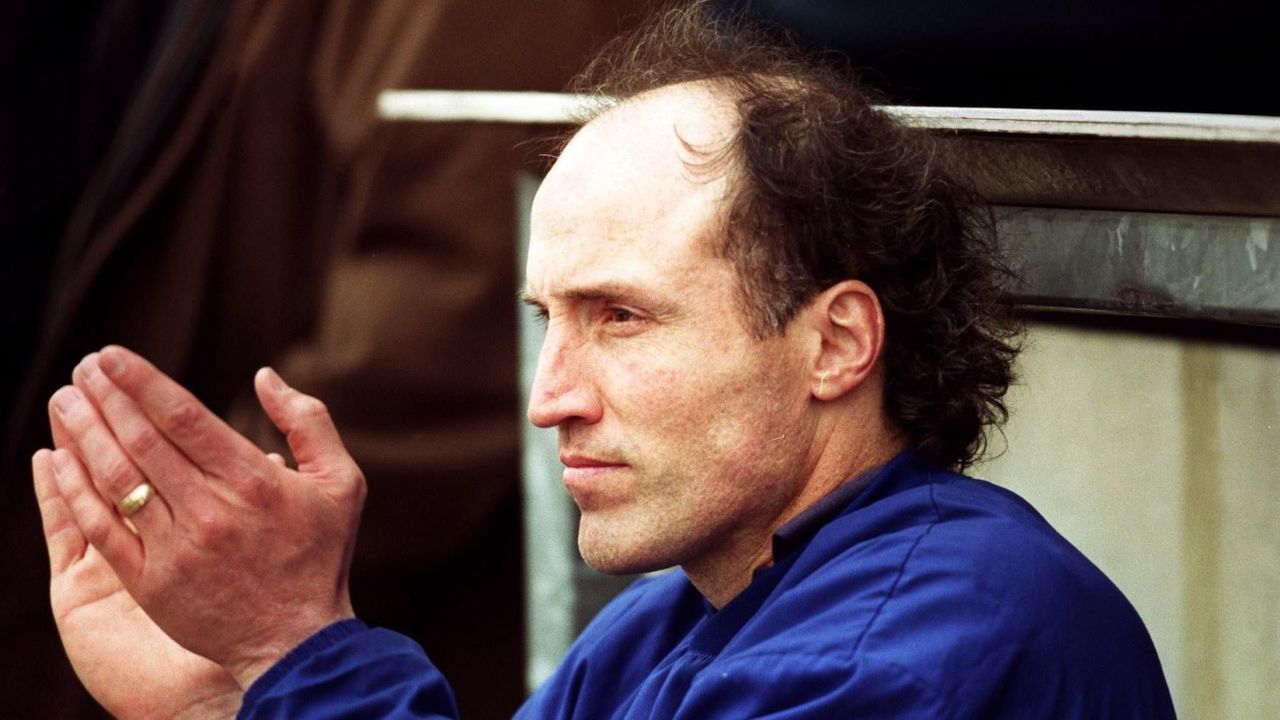

Smith, a former backup for the NFL’s New England Patriots, plunged into the world of soccer when he bought debt-riddled Chester City in 1999. He spent more time at the fourth-tier team’s training sessions than in his office, filling his notepad while he inquired about the purpose of certain drills.

Ratcliffe was mulling over a season-opening defeat to Barnet in the guts of the club’s Deva Stadium when Smith’s father Gerald – reportedly a key source of financing for the takeover – asked him for the whereabouts of someone named Keith.

“I said, ‘Keith who?’ He says, ‘Keith, the manager,'” Ratcliffe told theScore.

Ratcliffe thought quickly and mischievously directed Gerald to the dressing room for “Keith.” The turn of events bought the actual manager a few more hours until he met the Smiths the following morning.

A former defender who captained Everton during their greatest era, Ratcliffe felt “brain-dead” after that fateful meeting with Terry Smith and Gerald Smith. Ratcliffe irritated the younger Smith when he tried to excuse himself after four hours to spend time with his family on his day off.

“He got this scruffiest bit of paper that I’ve ever seen,” Ratcliffe described, “flattened it out, and proceeded to write on it. He gave it to me and it was a written warning.”

Ratcliffe was already plotting his exit from the club, a process that included him safeguarding players’ immediate futures with new contracts. The face-to-face encounter simply hastened his departure. He resigned shortly after the start of the 1999-2000 season, ending his first managerial role after over four years.

“If he was on fire on the other side of the road, I’d go and throw a log on him,” Ratcliffe said of Terry Smith.

Over his head

Chester City were on life support under their previous owner. Ratcliffe covered a £5,000 bill in 1998 to turn the stadium’s water back on and allow a friendly match to go ahead. He paid himself back with the gate receipts.

Darren Moss made his debut at 16 due to his obvious talent, but also, he suspects, because he was a cheap first-team option when his youth contract weighed in at just £42.50 a week.

The state of the club’s finances and the rather antiquated state of banking around the turn of millennia combined for a Mario Kart-style dash every payday.

“We’d get a cheque from the office after training and we’d all race down to the club’s bank branch in the middle of the town center so that we could make sure that you weren’t the last person,” ex-Chester midfielder Nick Richardson recalled. “Whoever was last one there might not have got paid.”

For Smith to deliver his ambitious promise of First Division football, he needed to ensure the club was on surer financial footing. Dan Brooks – a linebacker for one of the successful teams Smith coached in the UK’s American football circuit – was at a loose end in his native Canada when Smith invited him “to come and participate” in the Chester project.

“I marketed American football in a country where it really was not a priority. We had some success with that,” Brooks explained of his experience before he was named Chester’s commercial director. He also noted his position of marketing director for Frontierland, a theme park in the British seaside town of Morecambe that ceased operations in 2000.

Despite the off-field uncertainty, Smith was a regular fixture in training from the beginning. Ratcliffe claims Smith was going over his head to dictate when training started and finished even before his takeover of the club was ratified, and the owner was regularly inviting out-of-contract footballers to try out at Chester’s base.

“It was every week you’d get somebody come through the door,” Moss said. “You’d be like, ‘Fucking hell, who’s this now?’ And they’d be dreadful.”

Ratcliffe remembered an Icelandic trialist who Smith claimed could whip in dangerous crosses, was strong in the air, and was a good finisher.

“I’m thinking, ‘What’s he doing at Chester if he’s got all these qualities?'” Ratcliffe quipped.

Somewhat predictability, the trialist failed at Ratcliffe’s basic crossing, heading, and shooting drills while the rest of the squad went through its workouts nearby. Shaun Reid, the younger brother of then-Sunderland boss Peter Reid, watched in disbelief, and delivered a line which riffed on the trialist’s home nation sharing a name with a British discount frozen-food chain.

“Shaun shouted over to me, ‘So, gaffer. We got the lad in from Iceland, when’s the lad from Kwik Save coming in?'” Ratcliffe laughed. “(The joke) was right over Terry’s head.”

The Icelander’s unfortunate audition is one of Ratcliffe’s many tales of Smith’s transfer dealings. Ratcliffe says Smith signed an amateur player but paid him so little that he struggled to cover the one-hour round trip to training, while one American trialist had to stay the night at a local policeman’s house when Smith reneged on a contract offer and abruptly ended the player’s hotel reservation.

Smith also apparently decided to sanction the £10,000 sale of Andy Crosby to Brighton & Hove Albion. Ratcliffe said he’d recently rejected an offer worth twice that amount from Brighton.

“His face just turned blue,” Ratcliffe recalled of showing Smith the £20,000 bid he received via fax. “It just shows you, if you’re not conversing with your manager, you’re on a slippery slope.”

Ratcliffe thinks Brighton went behind his back because “they knew the state of the club.”

‘He’s going berserk’

Smith sensationally succeeded Ratcliffe at the team’s helm, trusting what he’d learned from around two months at the club’s training ground.

“All coaching is 90% the same, regardless of the sport,” Smith is widely quoted as saying after he assumed his self-assigned role.

“He loved to be in control of everything; hands-on with every single thing. I’d describe him as a bit of a control freak,” ex-player Moss shared.

Smith didn’t seem to use much of what he observed at Ratcliffe’s sessions.

“When Terry came in, the actual focus then shifted from 80% football and 20% set-pieces to 80% set-pieces and 20% football,” former midfielder Richardson estimated. Players would wear numerous layers to contend with the increased hours of standing around in the wet English weather.

It wasn’t only the strong set-play focus that harkened back to Smith’s American football roots. Moss said they played 11-v-11 gridiron in one session, where they threw the ball into the net instead of completing touchdowns. In an effort to boost leadership, Smith elected three captains: one each for defense, midfield, and attack. He also introduced prematch renditions of the Lord’s Prayer – a ritual that would be unique in any British sport.

Brooks, Smith’s marketing man, credits his friend as the most prepared coach he encountered during his American football career, and Chester’s unlikely manager was similarly meticulous in soccer. Moss remembered Smith would leave dossiers under each player’s hanger ahead of a match, with details such as set-piece positioning and information on opponents included. Moss said he and his teammates understood Smith worked long hours to prepare the personalized playbooks.

Smith’s competitiveness was undeniable and spilled over into him testing his strengths against those of his players. Richardson said there were a few gym sessions when Smith challenged the squad to lift a “fantastical weight,” but it would invariably turn into the players watching as Smith outdid everyone on the bench press.

“The bar would be bending,” Moss added. “He was a strong fella, to be fair.”

But aspects of Smith’s management clashed with his will to win.

He was disorganized for someone who tried to fill many roles. Martin Nash, the younger brother of two-time NBA MVP Steve Nash, was briefly on the club’s books and remembers there being “shit everywhere” in Smith’s car. Numerous people mentioned Smith’s office was seldom used and full of unopened letters.

And though the players were given little excuse to lapse on their set-piece routines, the nutritional preparation for games was counterproductive. There are accounts of McDonald’s, pizza, and cookies eaten as prematch meals, while Richardson remembered beans on toast at a greasy cafe under the highway before a 5-0 cup loss at top-tier Aston Villa.

The passionate yet rudderless nature of Smith’s regime didn’t foster respect among the squad. He became a bit of a laughing stock.

Moss describes an incident when someone locked Smith in the gym for an extended period.

“The groundsman heard him banging and came back over to get the keys,” Moss said. “He said, ‘You’re gonna have to get him out. He’s going berserk!’ I just remember Smith coming out and being red-faced – he was fuming. But he didn’t know who (locked him in), so he couldn’t put it on anyone.

Another unidentified player slashed Smith’s tires, and Richardson said defender Ally Pickering’s slapstick impersonation of the manager was a popular dressing-room act.

The poor relations between Smith and his players were unsustainable as the team sunk further into trouble.

‘He ran out of the dressing room’

Smith eventually relinquished the reins in January 2000 amid heavy pressure from supporters, after one win, one draw, and eight losses over their previous 10 outings. He expressed disappointment at how certain players and backroom staff let him take the blame for Chester being rooted the bottom of England’s professional pyramid, two points adrift of safety.

Ian Atkins – a manager with a strong lower-league resume – was given the unenviable task of trying to keep Chester City afloat under the guise of director of football.

“You were a manager because you ran the team, but Terry wanted that title as a manager,” Atkins told theScore.

The job title didn’t matter to Atkins. Smith assured him he would be in control of the senior side, and Atkins subsequently oversaw a swift squad overhaul with the support of assistant manager Gary Shelton and well-connected physio Joe Hinnigan. Some players were discarded and seasoned professionals were brought in. The tactical approach became more pragmatic.

Smith still wanted to be involved, though. He preferred to sit in the dugout alongside his coaching staff for matches, and he liked to warm up the goalkeeper before kickoff – even though Smith was often wearing a suit.

“Browny would take the piss,” Moss said of his former club colleague Wayne Brown. “Browny would be in goal lashing balls so Terry would have to run after them. Rather than playing them back to (Smith’s) feet, he’d zip them in, so he’d miscontrol it. He’d be collecting balls out the stands from the fans.”

But Atkins’ approach worked. An embarrassing 7-1 home loss to Brighton & Hove Albion in late February sparked a run of five wins and four draws in 12 matches, a spell in which Chester conceded only eight goals. Their fine springtime results remarkably put the Blues on course to avoid relegation on the final day of the season, but Smith was apparently unimpressed with the team’s style of play.

“We were having less possession than the opposition but winning,” Atkins said. “He couldn’t believe that his team were playing so open and having a lot more touches and attacking, but getting walloped every week.”

“He loathed the fact that people were giving me credit, Joe and Shelts credit, and the players credit,” Atkins added.

In the end, the upturn in results wasn’t enough. Chester City were relegated, plummeting out of England’s professional leagues for the first time in 69 years.

A lot conspired against them. One of Chester’s players decided to join the Trinidad & Tobago squad instead of playing in his club’s decisive final-day fixture. On the eve of that same match, another player was imprisoned for his alleged involvement in a fight outside a nightclub.

Meanwhile, Ratcliffe, the former manager now in charge of Shrewsbury, was seeking £200,000 in compensation from Chester.

And it was Ratcliffe’s Shrewsbury who won on the final day, securing their Division Three status while Chester lost theirs.

“It was a great feeling for me in one way, but a sad feeling in another,” Ratcliffe reflected. “Chester meant a lot to me.”

The crestfallen Chester players took exception when Smith tried to offer his post-match thoughts.

“In the dressing room after the game, he started to pipe up and a couple of the lads went for him,” Atkins said. “He ran out of the dressing room door and I’ve never seen him again.”

Atkins was already a popular figure with supporters and could’ve committed for another year with Chester, but felt he couldn’t match his ambitions when Smith handled the club’s operations. Graham Barrow, who was a fan favorite from his earlier stints as a player and a manager at Chester, was brought in to succeed Atkins, but Smith’s regime was already disintegrating.

Brooks is unsure what levels of abuse Smith dealt with from some fans. But the former commercial director told theScore that even he was in the firing line, as hosting press conferences and meetings with supporters had effectively made him “a secondary face of the organization.”

“I would get calls and people would be threatening my life and telling me to go home,” said Brooks, adding that a window was smashed at his house following the club’s relegation.

“I was looking over my shoulder. The threats and intimidation weighed heavily on me. I take things personally. I don’t have as thick a skin as some people … I didn’t know if (the threats) were going to be followed through or not.”

Brooks had an agreement with Smith that gave him an option to leave at the end of his first season, and he snatched at the opportunity. Smith himself was looking to take off when Chester were consigned to non-league football, with Brooks helping arrange meetings with potential buyers.

Smith eventually sold the club in October 2001 to Stephen Vaughan, a boxing promoter with links to infamous Liverpool gangsters. Vaughan was jailed for assaulting a police officer in 2013.

Chester City went bust in 2010, three years prior to Vaughan’s conviction, but a supporters’ group launched phoenix outfit Chester Football Club later that year. They now play in the sixth tier of England’s soccer ladder and protect themselves from shady investors by only inviting those who believe in the “ethos and the history of our club” to join the supporter-led ownership group.

Smith’s missteps, and those made by the owners that preceded and succeeded the American, can’t be made again.

“He didn’t realize what football meant to Chester City and the supporters. It was about him. Really, it was about him,” Atkins concluded. “He didn’t know football. He didn’t know anything about the club. He didn’t know anything whatsoever about players, how to win games of football.

“He didn’t know anything.”