The fan who scolded the Houston Astros through a megaphone this October was radicalized by the franchise’s stealing of signs, an ethical breach that Tim Kanter, like many people in baseball, considered unforgivable. He only thought up his response, though, because a different antagonist set him off first.

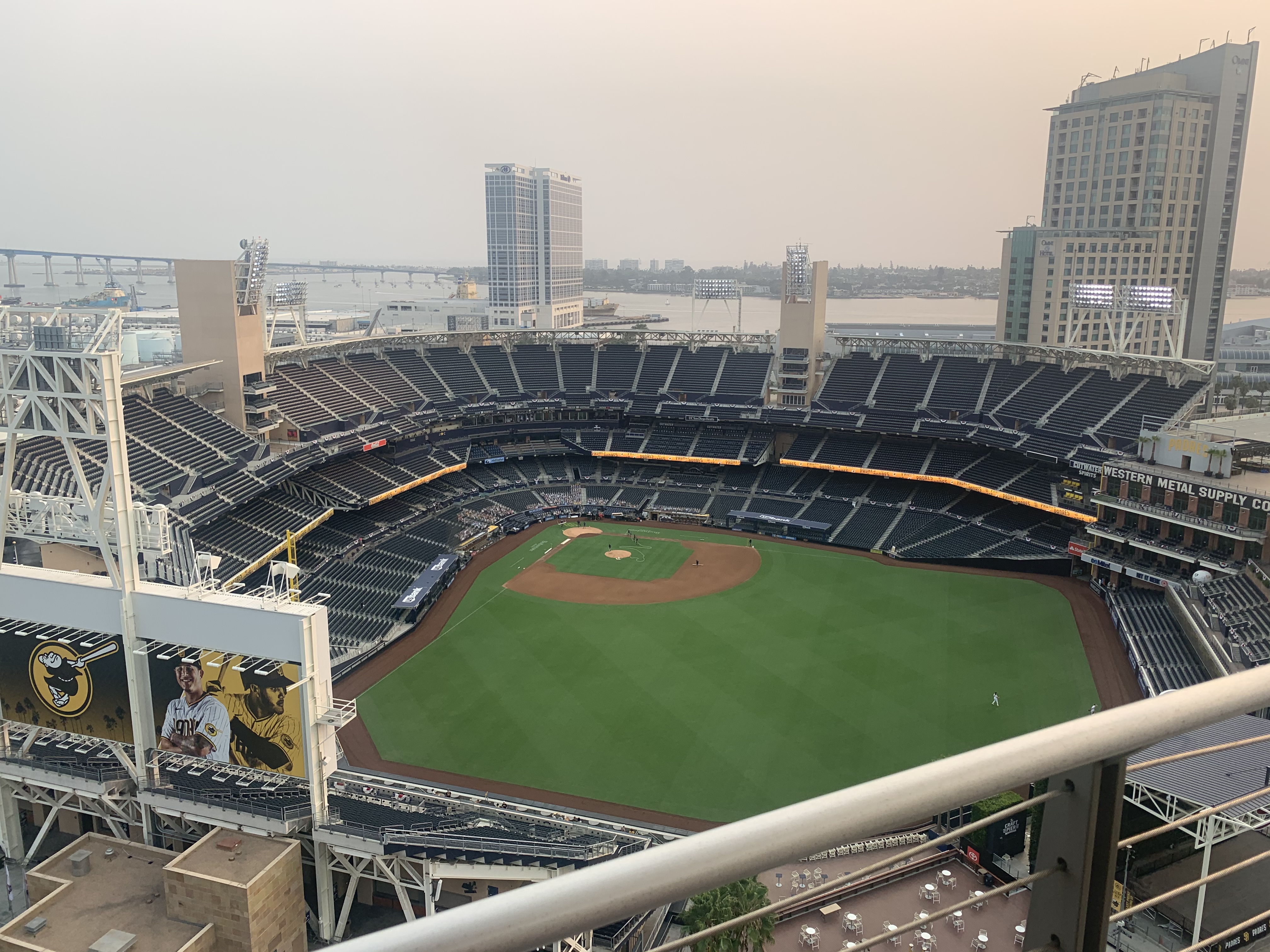

For that, the Astros can blame Matt Kemp. In 2014, the veteran outfielder was traded to the San Diego Padres and soon developed a reputation among the Petco Park faithful for trying, let’s say, less than his hardest. Memories of Kemp dogging it stuck with Kanter, a transplanted Chicagoan and a White Sox fan since childhood whose workplace overlooks the Padres’ stadium. He was out on the office balcony this summer when Kemp, now with the Colorado Rockies, stepped to the plate about 700 feet away, an open invitation for disgruntled onlookers to jeer him. So Kanter started booing.

“The left fielder turned around and looked up at me,” Kanter recalled recently.

As COVID-19 marauded the globe this year, no spectators were allowed inside Petco Park or any MLB venue until late in the postseason, magnifying the sounds of the game for players and coaches: the crack of the bat, the thud of ball meeting mitt, taunts bellowed from 13 stories above street level. Playoff series were held at neutral sites, including the ALCS in San Diego, and the Astros were among the last clubs standing. If one player had heard Kanter heckle Kemp without amplification …

That train of thought leads to the top of the fourth inning on Oct. 14. Game 4 between the Astros and Tampa Bay Rays was underway in front of zero paying fans. Kanter was alone on the balcony with sunflower seeds and a can of .394, a locally brewed pale ale named after Tony Gwynn’s best single-season batting average. He held his cellphone, on which he’d typed a short script, and a $200 megaphone, purchased with the help of family and friends.

Confident in the appliance’s power – Kanter had tested the megaphone by shouting down a canyon – he stood when the Astros took the field in the fourth inning. It was nighttime in Chicago, but not so late that his buddies there had gone to bed. Kanter was nervous but spoke clearly. “You all are a bunch of cheaters,” he read, loud enough to break through the silence the pandemic imposed.

“What is the word ‘sport’ without ‘fan’?” asked LeBron James. It was late March, a couple of weeks into the NBA’s coronavirus hiatus, and the Los Angeles Lakers superstar was speaking from his wine cellar to Richard Jefferson and Channing Frye, the retired players who headline the “Road Trippin'” podcast. James had proclaimed right before the shutdown that he wouldn’t compete in empty arenas, only to walk that back when it became clear the season couldn’t be completed otherwise. He had a sense of the spirit these games would lack: the crying, the joy, the motivation to quiet a wrathful road crowd.

“That’s what brings out the competitive side in players: to know that you’re going on the road in a hostile environment,” James said to Jefferson, Frye, and show host Allie Clifton. “Yes, you’re playing against that opponent in front of you. But you really want to kick the fans’ ass, too.”

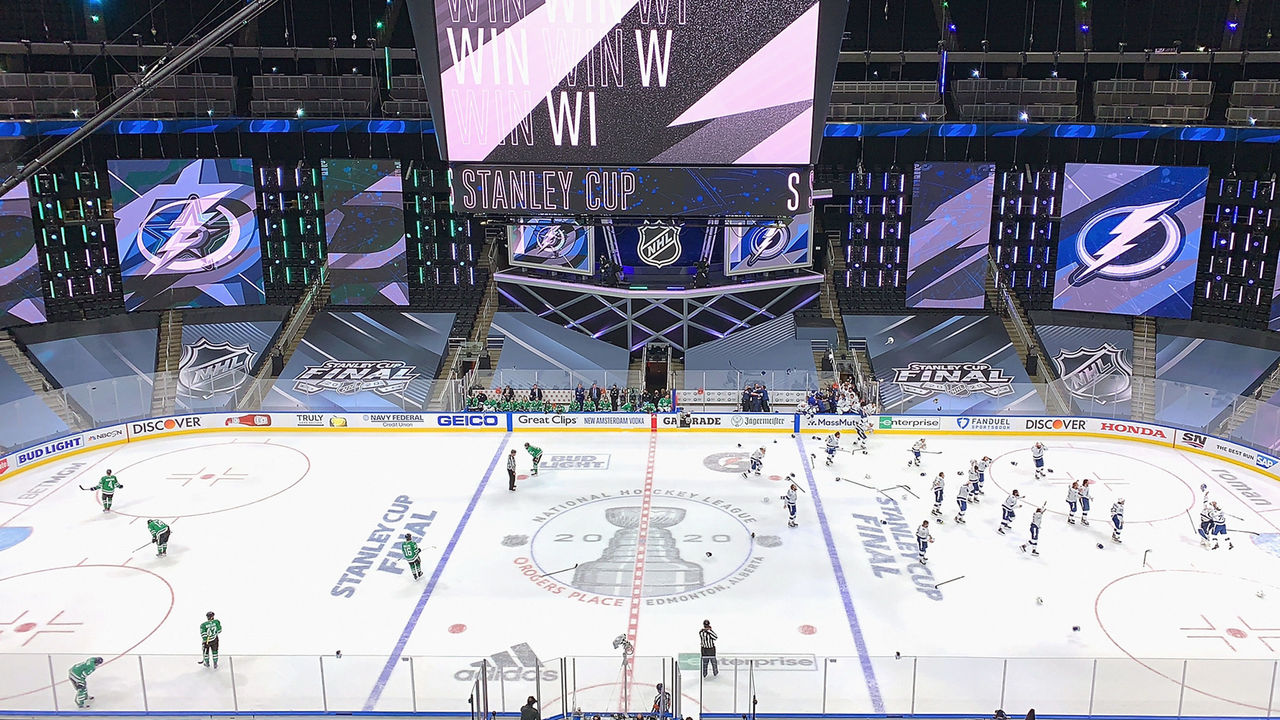

Deprived of the feeling, many teams spent months vying for wins and titles in sealed venues, showing viewers how weird it is to consume sports in a pandemic. The only seatholders in the NBA bubble were beamed into the building on 17-foot video screens. The only fans on hand for the NHL playoffs were the machine kind, masked to suit the occasion. Cardboard cutouts – of celebrities, of pets, of “South Park” characters in Denver – filled space at NFL and MLB games. Barred from the arena, fans lost the role they play in the theater of pro sports.

“No one was really able to speak for the people who (wanted to shame the Astros),” Kanter said. “Except for, you know, the yahoo with the megaphone.”

Across North America, sports’ biggest leagues and events were forced for the first time to anoint victors in sterile environments. No one got to attend the tennis US Open this summer, nor the rescheduled Masters in November. Some NFL and college football teams have welcomed spectators in limited numbers, and MLB sold 11,500 tickets to NLCS and World Series games in Texas. Far more often, though, canned chatter was broadcast to conceal stillness, and legendary venues or sparkling new sports palaces, from Lambeau Field to L.A.’s SoFi Stadium to Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas, were shut for the year.

2020 changed what it feels like to be a fan in the ways James forecasted. People couldn’t congregate with pals or by the tens of thousands to yell, despair, and berate opposing stars. James’ Lakers, like the Tampa Bay Lightning, triumphed in the postseason without once playing in their home city; the L.A. Dodgers took their last two steps on the championship ladder 20 miles west of Dallas. Everything was televised, but those among us who prize being in the stadium, bedecked in team gear or customized costume, endured a visceral loss.

“It’s like watching a commercial on TV for a steak restaurant,” said Mark Acasio, the Las Vegas Raiders superfan who goes by the nickname Gorilla Rilla. “You’re hungry and you can taste that food, but you can’t eat it.”

In recent weeks, theScore spoke to prominent fans and sports fandom scholars about the thrust of James’ question: How is engaging with sports different when everyone is holed up inside? Some noted that we still could witness games as they happened, preserving the spontaneity, and maybe much of the allure, of the experience. Before sports came back, market research company MRI Simmons concluded in June that U.S. fans felt disconnected without live action to watch, and that they missed the ready-made excuse to gather with family and friends.

If the resumption of games eased the first feeling, it didn’t restore interest to pre-COVID levels. With the exception of the National Women’s Soccer League, the first league to return to play in a bubble, TV sports ratings have been down across the board since the summer. Until things return to normal, we won’t know if this is the beginning of a trend or a reflection of how 2020 altered our usual patterns.

The coronavirus pauses that took hold in March utterly discombobulated everything in sports. LeBron won his fourth ring when NBA training camps are usually in session. Dustin Johnson slipped into the green jacket at Augusta during Week 10 of the NFL season. Indeed, every major team sport played high-stakes games opposite the NFL this fall, disrupting viewing habits like never before.

“That kind of compression basically causes an upset stomach,” said Joseph L. Price, a Whittier College professor emeritus who has studied the intersection of sports and religion. “The regularity is gone.”

Gone, too, when objects were all that populated the bleachers, was the pretense that the games were normal. Only the 2020 baseball season could have opened, in Los Angeles, with the destruction of Austin Donley’s cutout at the left-field wall.

Hey @Dodgers @will_smith30 do I get to keep the ball pic.twitter.com/wMeZrU2EYD

— Austin Donley (@adonley3) July 25, 2020

Weeks later, it happened again. Donley, 25, is a Dodgers devotee whose family usually attends up to 70 home games a year, and during L.A.’s first series in July, catcher Will Smith beaned his cutout with a home run. The likeness was left halfway decapitated, and Smith mailed Donley a signed bat for the trouble. Then, early in September, Mookie Betts deposited another dinger in Donley’s virtual lap.

“To have been even a fraction of a fraction of a percent of the story of the year is so cool to me,” said Donley, whose tweets about the homers went viral.

I need to go buy a lottery ticket @mookiebetts @Dodgers pic.twitter.com/oYJWmHeYW1

— Austin Donley (@adonley3) September 5, 2020

There are advantages to tuning in from afar. Acasio prefers the frenzy of the Black Hole, but removing his gorilla mask to watch the Raiders on TV has let him see and analyze the game better. Taylor Soper, a Portland Trail Blazers fan and the managing editor of the tech publication GeekWire, wrote favorably in August about his night as an NBA virtual spectator, in which his upper body appeared via LED monitor near center court of a Blazers-Lakers playoff matchup. The stream he watched was smooth, Soper said in an interview, and he liked chatting with his section mates from the comfort of his apartment, which approximated the camaraderie of the arena.

As James divined from the start of the NBA break, it’s harder to recreate a crowd’s excitement, or nerves, or the noise that swells when pressure mounts. Reflecting on baseball’s pandemic summer, Price said the cardboard interlopers in the stands lacked a crucial third dimension: “I think the passion that fans show is much deeper than length and width.” Lethargy is all the more apparent when, say, 65,000 chairs go unused at Allegiant Stadium, as Daniel Wann noticed when he turned on the Raiders game one recent Sunday night.

“(Teams build) these stadiums with tens of thousands of seats,” said Wann, a psychology professor at Murray State University whose research focuses on sports fandom. “That tells you all you need to know. They expect fans to be a part of it, and when they’re not, it just feels like something is missing.”

Just as the year’s oddities have influenced the feel of fandom, so too will 2020 shape its future. This summer, as COVID-19 hiatuses ended, 75% of respondents to a Fan Three Sixty survey said they’d only attend live games again if venues established new safety protocols, be they “extreme” or as basic as installing more dispensers for hand sanitizer. Personal mileage will vary, but those results suggest it’ll take some convincing for the masses to return.

The next time spectators are able to flock to Allegiant or Lambeau, to Petco Park or basketball and hockey arenas everywhere, the operators of these venues will have to balance substance and perception, industry executives said in interviews. That means implementing sound safety measures and making it obvious those measures are in place.

“When you’re coming back from COVID, the really important thing that you need to have as a fan is clear information,” said Adam Goodyer, the founder and CEO of Realife Tech, a data-aggregation platform that’s designed to streamline how spectators move through live events. “Where do I go? How do I get there? How do I stay safe?”

From security lines to concession stands, we probably can expect many aspects of the live experience to become increasingly touchless.

Cash and paper tickets may soon be relics. The same goes for food and condiment buffets, as well as the practice of vendors and strangers passing beers down a long row. (At Tottenham home matches in London, Realife’s technology coordinates mobile orders through the team app, notifying people where and when to collect their order.) Hygienic changes could include the removal of restroom doors; sinks could be configured to time handwashes in line with health advice. Venues might hire more janitorial staff and, during games, have them stand and work in plain sight.

While cardboard cutouts and pixelated faces tend not to move much, actual spectators meander and queue around the concourse, creating logjams. Stadiums of the future could be built to maximize spaciousness and physical distance, but adjustments are likely to take hold in the meantime. To prevent free-for-all circulation, people could be instructed to walk in aisle formation and restricted to certain zones of the building. Software can be used to monitor the number of people in a given space, alerting venue staff to excessive crowding.

“They have to have this insight now in terms of where crowds are, how they’re moving, where to push them in terms of distribution,” said Zachary Klima, the founder and CEO of the AI startup WaitTime, which fulfills this function for the San Francisco 49ers, Miami Heat, and Buffalo Sabres, among other clients. “Everything that was once a ‘nice to have’ is now a ‘need to have.'”

COVID-19 precautions forced people to live digitally, and post-pandemic, away from stadiums, emergent technology could change how we tune into sports. Soper sees potential for the NBA to expand its foray into virtual spectatorship – by enabling food orders through the platform, for instance, or by charging people to watch that way. James Carwana, the general manager of Intel Sports, sees potential for volumetric video to upend the traditional sports telecast. He envisions a future where this 3D tech, which Intel has installed at NFL and NBA venues, captures the action from 360 degrees and lets fans personalize the perspective from which they consume games: the quarterback’s, the defense’s, innumerable others.

More than usual this coming season, NHL chief content officer Steve Mayer said, his league is going to try to entertain fans with clever material on social media. Over the summer, Mayer was in charge of managing hockey’s 2020 playoff hubs, where game operations staff were given rein to experiment with in-arena messaging. “At the conclusion of tonight’s game,” one note on the video board in Edmonton read, “please exit your couch safely.”

Words to live by in 2020. In September, when the Lightning blanked the Dallas Stars to win the NHL final in six games, the workers who kept the bubble running were the only people there to see it up close.

“One day,” Mayer said, still processing the reality months later, “we’ll (remember) there were maybe 100 people who were actually physically in the bubble watching the Stanley Cup Final happen.”

Seventy-two days after the NBA’s own title series ended, the 2020-21 regular season is set to start Tuesday, with the NHL’s expected to follow in January. Early games won’t be as tense as those that unfolded in hubs, and rather than be isolated from society, players will live at home and stay at hotels in road cities. But one fact of bubble life persists in the immediate term. In many cases, teams don’t plan to permit spectators.

Two scenarios would allow fans to return to arenas safely, Zachary Binney, an epidemiologist at Oxford College of Emory University, said in a recent interview. In one, attendance is limited to those people who’ve received a COVID-19 vaccine. Short of that requirement, he said, some critical mass of the population has to be vaccinated or immune to be sure that indoor games won’t spark or compound an outbreak.

No other option is prudent right now, Binney said. If positive case counts are low in a given area, and if rapid, accurate tests can be deployed on-site to screen spectators for COVID-19 right before they enter, maybe it’ll be safe in the spring for some arenas to open at limited capacity. For the moment, he preaches caution and patience.

“You can always get sick from going to an NBA game. What we want to do is make sure that we’re getting back down to that risk that we had all agreed – before (COVID-19) – was acceptable,” Binney said. “Not 100% of people have to be vaccinated to get to that, but some appreciable portion that will take months. Very possibly through the end of the next NBA and NHL seasons.”

Baseball season is still a ways off, leaving time for diehards like Donley to think about how 2020 redefined their fandom. Once the domain of streakers, fair-ball interferers, and escaped cats, fans no longer had to visit the field to blow up for 15 minutes. As the man behind the magnetic Dodgers cutout wrote in October, in a blog post for the website Simply A Fan, “I’ve joked with people that this is the least possible effort one could expend to go famous: having a picture of yourself getting hit by a ball at a game you were never at.”

Donley was at home with his parents and girlfriend the night of Oct. 27, when Julio Urias struck out Willy Adames in Texas to seal the Dodgers’ first championship since 1988. That they hadn’t played in L.A. since the wild-card round didn’t dampen his joy, Donley said, considering the glum alternative that the pandemic could have wrought: the season being canceled, Betts leaving in free agency, the title drought continuing unabated.

Randi Radcliffe, a Dodgers podcaster and superfan who went to more than 100 games in 2018 and 2019, didn’t expect to kneel on the ground, her hands shaking and tears falling, as Urias hurled his last, triumphant strike. Following this season from afar was hard, she said, without friends by her side or fans anywhere in sight. Yet she looked forward to every game, and familiar emotions surfaced for the World Series. Anxiety about the stakes. Anger when the Rays walked off with Game 4. Dread that this, again, wouldn’t be the Dodgers’ time.

In the end, one thing made a surreal year feel real, Radcliffe said: “Seeing them finally hold that trophy above their heads.”

Before the Dodgers and Rays descended on Texas for the World Series, when Houston still had championship ambitions, few viewers got as near the playoffs as Kanter. On his San Diego office balcony, over his megaphone, he called out Jose Altuve for cheating, and then Carlos Correa, and George Springer, and Alex Bregman. It caught the attention of reporters covering the ALCS, and he got to explain his actions to The New York Times.

Not that personal notoriety was the point, he said: “The point was for the Astros to hear it.” Once that happened, Kanter set down his megaphone and took a seat, content to savor his sunflower seeds and perch above the park.

“I felt incredibly fortunate to be able to have that vantage point,” Kanter said. “I figured I may as well enjoy watching the game for as long as I could.”

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.